Project Description

The ‘Creek Filtration Systems’ Trial is a Lord Mayor’s deliverable under the ‘Cleaner Waterways Initiative’. It is a four-year trial of a range of filtration systems aimed to enhance waterway health in four of Brisbane’s major catchments. The creek filtration trial at Glindermann Park is one of eight systems being trialled in these catchments.

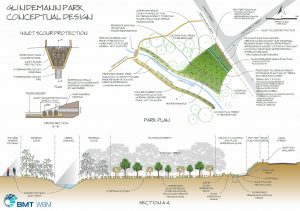

The Glindermann Park creek filtration trial works by slowing down and filtering polluted stormwater from an urban catchment before it discharges to a tributary of Norman Creek. Stormwater which flows from the nearby roads, footpaths and residential allotments, is collected by the existing pit and pipe network and ‘day-lighted’ (removing the existing pipe), before being discharged into the filtration system.

At the inlet to the system a rocky ‘scour protection area’ ensures that fast flowing water is slowed down and does not erode the soil or wash away plants. The stormwater then spreads out over a sandy swale full of plants. The swale is designed to distribute flows and prevent ponding so that mosquitos can’t breed in the system. The sand that the plants grow in was specially blended to assist stormwater to seep into the ground, sustain plants and assist in removing pollutants (sediment, nutrients, oils and heavy metals) from the stormwater.

When the swale fills with stormwater it overtops a weir (or ‘level spreader’). As the name suggests this feature spreads flows evenly over a densely planted ‘filtering forest’. In the filtering forest the plants and soils further help to cleanse the stormwater and slow it down so that it more closely mimics pre-development flows. The stormwater and associated nutrients help to sustain and enrich the plants so watering and fertilising is not required after establishment. This saves precious drinking water.

Containment bunds on either side of the filtering forest help to keep the stormwater where it’s supposed to flow and ensures maximum filtration of the stormwater through the forest. The bunds also assist in keeping nearby turfed areas free from ponding water meaning turf areas are usable after rainfall.

Stepping stones through the filtering forest and signage help to educate residents about the system and encourage interaction with the filtration system.

Objectives

The objectives of the Creek Filtration Trial program are to treat and remove pollutants in stormwater runoff at priority locations, demonstrate the value of creek filtration systems in terms of cost and benefit and showcase Council’s commitment to cleaner waterways.

More broadly, the projects seek to demonstrate how the multiple objectives envisioned by Council’s WaterSmart Strategy, Our Shared Vision: Living in Brisbane 2026, and the Norman Creek 2026 Master Plan can be realised through small scale, simple retrofit projects.

Key Challenges

The key design challenge faced was a lack of adequate data with respect to existing services. As-constructed drawings were not entirely accurate. As a result, works stalled during construction as level issues were resolved. Some of these issues could have been resolved more easily with closer construction supervision. For example, the civil engineers working on the project had a good appreciation of the services and earthworks design and could have directed the construction crew on how to make minor changes during construction to account for actual service locations/depths.

Key Lessons

- The Glindermann Park creek filtration trial is well received by the local community.

- Creek filtration systems can be effective yet relatively cheap and deliver good value for money.

- Simple alternatives exist to traditional “bioretention” systems. These alternatives can potentially deliver equivalent or better outcomes to those systems. This creek filtration system provides water quality treatment in a previously unused open space, using a less expensive, low tech solution than standard a bioretention system. At the same time it contributed to restoring a stretch of riparian vegetation.

- Retrofit projects by nature will generally result in conflicts with existing services. To minimise issues associated with such services a full survey, including the location of underground services, should be undertaken prior to design. This should include a much larger area around the expected location of works to allow flexibility in design.

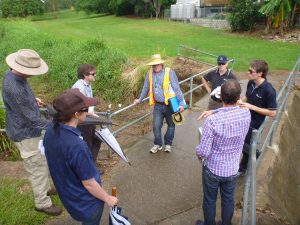

- Engaging a multi-disciplinary team will deliver more holistic outcomes for the community.

- Close liaison between the design team and Council during concept design ensures a common understanding of project aims and options for design which responds to project objectives.

- The design team should be involved in supervision and certification during the construction and establishments stages. Minor issues which arose during construction could have been more easily resolved if the design team had the opportunity to ensure that the design intent was maintained throughout construction.

What makes this project innovative?

- The Glindermann Park Creek Filtration system is one of the few examples of vegetated stormwater treatment assets specifically designed to actively encourage the community to enter and engage with such an asset. By doing so, the system blurs the line between drainage corridors and parks and provides a good case study for how to integrate stormwater management with open space. In this case, integration is achieved through something as simple as the installing stepping stones. This project demonstrates that integration can be achieved easily with benefits expected to outweigh costs.

- This is a pioneering example of how to design a combined swale/level spreader system specifically to achieve even flow distribution across a vegetated stormwater quality treatment system. Even flow distribution is critical in such systems to maximise water quality improvements and reduce risks of scouring.

- Spreading flows across a vegetated area is a return to the use of riparian corridors for multiple benefits including stormwater quality treatment. It helps to remind practitioners of possibilities other than current best practice bioretention and wetlands as a means to treat stormwater.

- By avoiding the hard engineering structures typical of current best practice bioretention systems (i.e. overflow pits, concrete sediment forebays and drainage pipes), the design helped to reduce construction costs, complexity, carbon footprint and risks to water quality from chemicals leaching from plastics and concrete used in those structural elements.

- By working with the natural topography, earthworks were limited which also helped to reduce costs and the system’s carbon footprint. Similarly, earthworks were reduced by avoiding excavating large areas to install filter media typical of current best practice bioretention systems.

- A conscious decision was made not to install drainage pipes in the infiltration trench or filtering forest instead trialling the effectiveness of exfiltration as a means to avoid ponding. The base of the exfiltration trench and subgrade of the filtering forest were ripped/ cultivated to maximise infiltration to the subsoils. This approach is often used in landscape design but not traditionally applied to vegetated stormwater systems.

Other Comments

- Shortly after construction, a blocked sewer caused sewerage to overflow into the filtering forest. The filtering forest intercepted the overflows and minimised the amount of pollutants entering the waterways. The plants benefited from the additional water and nutrients. The system did not show any negative impacts from the event.

- Although there is an existing sewer located underneath the filtering forest (a manhole can be seen in the filtering forest), stormwater inflow to the sewerage system was not a concern. Water levels in the creek rise very quickly during rainfall. These levels are higher than the sewerage pipe, even during minor rainfall events. The filtration system will therefore result in little or no additional flows into the sewerage pipe.

- Since the system was constructed, observations during and after rainfall have shown that:

- The inlet scour protection area is functioning well. No scouring has been observed.

- The swale is functioning well without any excessive ponding observed following storm events.

- Although velocities through the system are low and mulch used was of the non-floating variety, holding down mulch with jute mesh (pinned down at 500mm centres) is important. Some of the mulch which was added later on top of the jute mesh was washed away during storms. The mulch beneath the mesh remained in place.

- The concrete level spreader was not ‘keyed’ into the bunds during construction. Despite this, there is no immediate evidence of scouring, possibly because of the mulch and jute mesh which have helped to stabilise the area. Options to rectify the weir are being considered.

- Although concrete was used to fix the stepping stones in place, some of the stepping stones have become loose and require rectification.

- The community read the information signage provided. Local residents visit the system during storm events to watch the system ‘in action’.

- Photos shown in this case study are of the system immediately after planting.

Contact

Brad Dalrymple or Paul Dubowski (BMT WBM)

Mark Gibson (Brisbane City Council)

Responsible Authority

Brisbane City Council

Designers

Brad Dalrymple and Paul Dubowski (BMT WBM) in collaboration with: Tim Evans, Ray Wassenberg & Ken Baddiley (Civil Dimensions); Damian Thompson and TJ Joseph (LAT 27) and Malcolm Eadie (E2 Design Lab). Mark Gibson and Stefanie Stanley from Brisbane City Council also contributed valuable input into design.

Contractors

Brisbane City Council

Project Timeframes

Concept and detailed designs were completed between February 2013 and May 2013

Construction was completed throughout June 2013

Estimated Costs

In accordance with the principles of water sensitive urban design, one of the key project aims was to minimise development costs while maximising benefits. Hard structural elements were largely avoided. Brisbane City Council invested AUD$135,000 for the construction of this project.

Tags

http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/environment-waste/water/creek-filtration-systems/index.htm